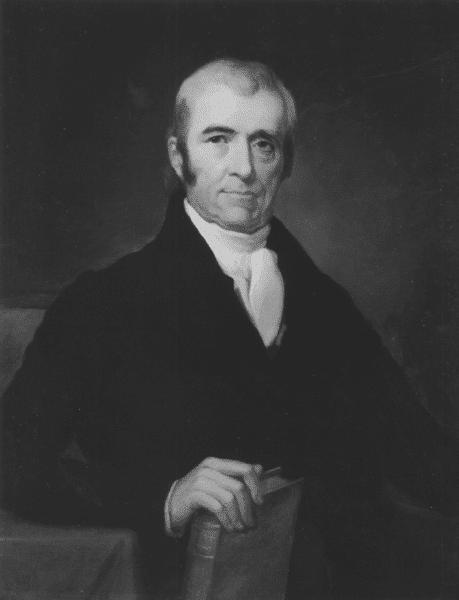

As chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835, John Marshall of Virginia played a formative role in establishing American federalism as it existed prior to the ratification of the ;Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. His was a balanced federalism that conceded sufficient power to the federal government that it could adequately perform its national and international functions, but at the same time sought to preserve broad and extensive residual state powers sufficient for their traditional and vital task of protecting the health, welfare, and safety of their citizens. Simultaneously, Marshall enhanced the position of the U.S. Supreme Court as the primary arbiter of disputes concerning federalism, and as the constitutional watchdog for an effective and functional national government in the United States.

A Federalist in political alignment and a participating member of the Virginia convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in June 1788, Chief Justice Marshall belonged to the moderate wing of the Federalist Party. As such, he would have rejected out-of-hand former Chief Justice John Jay’s view that upon the ratification of the Constitution, the states were relegated to the status of being mere administrative instruments of the central government. At the same time Marshall recognized that the Constitution divided sovereign powers between the federal government and the states, subject to the provisions of the Supremacy Clause (Article VI), which subordinated state initiatives to those of the federal government in three specific instances: (1) when state laws or actions were repugnant to the Constitution, (2) when state laws or actions were contrary to congressional statutes enacted pursuant to the Constitution, and (3) when state laws or actions were in conflict with treaties entered into by the United States, either before or after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

Contents[hide]

- 1 FEDERAL AND STATE POWERS IN LIGHT OF THE SUPREMACY CLAUSE

- 2 ECONOMIC FEDERALISM

- 3 JUDICIAL FEDERALISM

FEDERAL AND STATE POWERS IN LIGHT OF THE SUPREMACY CLAUSE

In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Marshall resolved many of the major federalism questions that arose before the American Civil War. The case involved the constitutionality of a Maryland state tax imposed upon the bank note issue of the Second Bank of the United States. In response to arguments by Maryland’s attorneys, he firmly rejected the compact theory of union. This doctrine held that since state ratifying conventions had approved the new Constitution, the ratification was an action by the states. To the contrary, Marshall held that the people of the United States, even though they acted through state conventions, were the active agents in establishing the new government. He would return to that position later in his opinion when he pointed out that to permit Maryland to tax the activities of the federal bank would be to subject the interests of the people of the United States to the whims of the voters of each individual state. Implicit in Marshall’s decision was his rejection of other arguments that urged that the Articles of Confederation, with their narrow grant of governmental powers to the central government, should form a basis for construing what he viewed as the broader federal authorizations of the Constitution.

The chief justice also spelled out the doctrine of implied, or incidental, powers that held that within congressional powers expressly enumerated in the Constitution, there were logically included adequate means to effectuate those grants of authority. Thus the establishment of a national bank grew out of the federal government’s taxing and spending powers, as well as other powers including the war power. Drawing from the argument of William Wirt, he pointed out that all possible means of effectuating federal enumerated powers could not be included within the Constitution’s text. If such a thing had been attempted, the document would have exhibited the “prolixity of a legal code, and could scarcely be embraced by the human mind.” Only the major principles were stated in the Constitution’s text, and the minor details were left to be deduced from the nature of the Constitution’s objectives. Conceding that the federal government was a sovereign of limited authority, Marshall insisted that within the scope of that constitutional grant, its actions were supreme and state action to the contrary was void.

McCulloch v. Maryland also established the meaning of the Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8) of the Constitution. The chief justice pointed out that while the term “necessary” might be viewed as meaning absolutely necessary, it did not necessarily carry this restrictive connotation. Indeed, in the placement of the clause within positive grants of power to Congress, the framers of the Constitution exhibited an intention to use the word “necessary” in a broad, enabling sense rather than a narrow and limiting context. Their intention was also demonstrated by the use of the term “absolutely necessary” in Article I, Section 10, to limit state authority to enact laws in the nature of taxes on exports or imports. Failure to so limit the use of “necessary” in Section 8 was further evidence of an intention to permit a less restrictive use of the word. Adopting a so-called loose construction of the Necessary and Proper Clause, he observed, “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consistent with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.”

ECONOMIC FEDERALISM

Since the motivating pressures toward the adoption of a new constitution included the need to integrate the American states in what would come to be called a “common market,” the federal Constitution contained two provisions that were particularly important for economic integration. These were the Contract Clause, which prohibited the states from enacting laws that would impair the obligation of contracts, and the grant of power to Congress to regulate commerce among the states, as well as foreign commerce and trade with the Indian tribes.

The Contract Clause served as a guarantee that the states could not enact laws that destroyed property rights based on contractual provisions. It was designed to prevent state limitations upon the collection of commercial debts, but on behalf of the Supreme Court John Marshall extended its protection to vested rights acquired under state land grants (Fletcher v. Peck 1810) and corporate charters (Dartmouth College v. Woodward 1819). With the Privileges and Immunities Clause (Article IV, Section 2), the Contract Clause operated to restrain the states from favoring their economic interests above those of the other states. Under the Articles of Confederation government (1781–89), state protective tariffs and competitive disadvantages imposed on nonresidents had produced economic warfare among the American states. Interstate trade foundered, and commercial chaos discouraged European investment in infant business ventures. Marshall’s elaboration of the scope and meaning of the Contract Clause did much to enhance federal power and American economic development.

Even more important to the evolution of a federal system was the Constitution’s Interstate Commerce Clause. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the federal Constitution gave Congress broad powers over trade within the boundaries of the United States. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), Marshall defined the commerce power and explained the constitutional division of federal and state authority over commercial activity. Gibbons brought before the Supreme Court the constitutionality of New York State’s grant of a monopoly over steamboat navigation of the Hudson River, New York Harbor, and all adjacent waterways. The case attracted national attention because it involved the threat that one strategically located state might unilaterally close a river to both interstate and foreign commerce. Of greatest concern was trade on the Mississippi River, which was largely dependent upon free access to the Gulf of Mexico.

At the outset of his Gibbons opinion, the chief justice restated his McCulloch v. Maryland position in regard to federalism. The enumerated powers in the Constitution should be liberally construed, and it was contrary to the overall meaning of the Constitution that strict judicial construction should destroy the ability of the national government to function effectively. He defined “commerce” broadly to include navigation; similarly, he examined the use of the term “among” to suggest that while strictly internal activity within a state was not within the federal power, economic activity that involved one or more states would be subject to congressional regulation. Thus activity within one state that was related to trade with other states, whether adjacent or distant from its boundaries, would be subject to the commerce power.

Although Marshall provided a broad construction of the commerce power, he stopped short of calling it exclusive. Instead he looked to the modes in which federal and state powers were interconnected. The taxing power was concurrent, since both state and federal governments needed access to taxes for their support. Similarly, although the commerce power was clearly vested in the United States, the states in the exercise of their traditional authority to regulate police, domestic trade, and matters of public health and welfare might touch upon areas of interstate or foreign commerce. In situations where there was direct conflict between state and federal power, the supremacy clause of the federal Constitution would require invalidation of the state legislation or action. However, in Gibbons the New York legislation regulated commerce and purported to do the very thing that the Constitution assigned to Congress, hence the monopoly was invalid. Marshall’s analysis began with seeking the authority in the Constitution for both federal and state action. Having identified the state’s source of power as being within the so-called police powers of the state, he proceeded to consider the degree to which the state action interfered with Congress’s regulation of commerce. If the state action conflicted with the commerce power, the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause required that the state action be invalidated. What the chief justice left unsaid was the fact that it was the U.S. Supreme Court that would ultimately determine what state actions would be held invalid as infringements of Congress’s commerce power. Subsequently, in Wilson v. Black Bird Creek Marsh Company 1829), he would return to the federalism aspect of Gibbons. When a state dammed a navigable creek to enhance public health and prevent flooding, Marshall upheld the state police power. He noted that Congress had legislated on the subject and that the Delaware statute could not be considered repugnant to the Commerce Clause in its “dormant” state. In other words, in the absence of congressional legislation, the state’s damming the creek was not contrary to Congress’s unexercised power as expressed solely in the Constitution itself. Taken together, Gibbons and Wilson illustrate the flexible quality of Marshall’s federalism in commercial matters. In the absence of a direct conflict—that is, a state doing what Congress was authorized to do by the Constitution—he was willing to seek constitutional authorizations within a state’s broad and residual governing powers, and, in appropriate cases, to uphold the validity of state legislation.

JUDICIAL FEDERALISM

The Supreme Court under John Marshall, and all of the Courts that followed it, played a crucial role in the establishment and operation of the federal system. Under the Constitution the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction (trial court powers) to decide cases in which the states sued each other, as well as actions brought against foreign diplomats. The Court was also empowered to try boundary disputes between the states, a function predating the Federal Constitution that was conferred upon the Confederation Congress by the Articles of Confederation. The Supreme Court’s trial authority in cases involving foreign ambassadors and diplomats was granted by the Constitution to avoid the embarrassment of state courts meddling in international affairs. Under John Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803), this original jurisdiction provided by the Constitution might not be expanded or limited by congressional legislation.

Appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court was subject to legislative control by Congress, as was the creation and regulation of federal courts subordinate to the Supreme Court. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established lower federal courts that were given broad authority to adjudicate cases involving federal civil or criminal laws, to decide proceedings in admiralty, to determine certain cases where the litigants were citizens of different states, and to decide cases in which the United States was a party. John Marshall viewed these lower federal courts as having limited jurisdiction, defined by precise terms of the congressional statutes (Kempe’s Lessee v. Kennedy 1809). From these federal courts the Supreme Court was, in certain cases, authorized to exercise appellate review. Thus the Supreme Court was the final court in matters of law and equity decided within the federal court system, including territorial courts and those of the District of Columbia.

The 1789 Judiciary Act also provided for the Supreme Court to exercise appellate review over certain decisions of the highest courts of the states that had authority to decide a matter. This type of review, patterned in part after the authority of the English Privy Council to hear appeals from the American colonies, was critical to the operation of American federalism. The supremacy clause demanded that the Supreme Court be the final arbiter of so-called federal questions, broadly defined as matters involving the federal Constitution, statutes enacted pursuant to the Constitution, and treaties entered into by the United States. In Chief Justice Marshall’s day whenever a claim raising a federal question was denied by the state court, an appeal or writ of error might be brought before the Supreme Court of the United States. Appellate review of state court decisions was a controversial matter in the early republic. Virginia’s defiance of the Supreme Court’s decision of the Fairfax land cases (Fairfax’s Devisee v. Hunter’s Lessee 1812) triggered the Marshall Court’s decision in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), in which Associate Justice Joseph Story’s opinion set forth a strongly persuasive argument that the federal union would be a virtual nullity if every state were permitted to be the last resort in answering federal questions. The controversy involved Virginia realty that was owned by the estate of Lord Fairfax at the opening of the Revolution, but that Virginia argued had been escheated to the state when Fairfax died and left a British heir to inherit. Thus the case involved the interpretation of the Peace Treaty of 1783 and the Jay Treaty of 1794; permitting a state court decision to stand without review by the U.S. Supreme Court would mean subjecting international treaties to interpretation and enforcement by each state’s judiciary.

John Marshall’s support for this comprehensive view of federal court authority appears most clearly in the case of Cohens v. Virginia (1821), where Virginia again challenged the appellate jurisdiction of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Cohen brothers, a Norfolk partnership, were convicted in a Virginia trial court of selling lottery tickets issued by the District of Columbia government. Marshall’s opinion dealt with whether the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to issue a writ of error to the Norfolk City Hustings Court, the Virginia court having initial and final jurisdiction to decide the case. The Commonwealth of Virginia argued that the Eleventh Amendment prohibited the U.S. Supreme Court from exercising jurisdiction, since the amendment exempted from federal court authority any cases in which a state of the union was a party. The chief justice rejected this view of the case, pointing out that Virginia was the prosecutor in the Hustings Court and the amendment exempted only cases in which a state was the defendant. Appellate review was not included within the amendment’s denial of federal court jurisdiction. Returning to a theme already stated in McCulloch, he pointed out that denying such appellate review by the Supreme Court, and leaving a state court with the final determination, would in federal terms be subjecting the rights of all U.S. citizens to state courts not necessarily their own. In addition, as Justice Story indicated in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, the Constitution, federal statutes, and treaties would receive as many interpretations as there were states.

According to Marshall, the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction under Article III was based on either of two factors: (1) the status of the parties, or (2) the character of the cause. In Cohens the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction depended not upon the parties to the case, but rather upon the nature of the cause—that it brought into question the construction of the statutes of the United States. He concluded that “the judicial power . . . extends to all cases arising under the constitution or a law of the United States, whoever may be the parties.” Therefore, Virginia could not claim exemption from jurisdiction by virtue of its status as a state. In effect, Marshall held that the resolution of federal questions was primary, and the status of the parties to the case was secondary. The net effect was to extend the authority of the Supreme Court to deal with federal questions, thereby advancing federal judicial power at the expense of retained powers of the states.

Chief Justice Marshall also rejected the argument that the appellate power of the Supreme Court might not be exercised in any case over the judgment of a state court. Indeed, the Supremacy Clause’s demand that the constitution and laws of a state not be repugnant to the Constitution and laws of the United States made it essential that the U.S. Supreme Court have appellate jurisdiction over the state courts when federal questions arose. This was not only consistent with the Constitution and Section 25 of the Judiciary Act, but also in accord with the spirit and intent of the Constitution and its framers.

Based on these considerations, Marshall held that the Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction to review the conviction of the Cohen brothers. Moving on to the merits of the case, he pointed out that Congress in enacting the District of Columbia lottery law had not made any express provision that the anti-lottery laws of the various states were suspended or repealed by the federal statute. It was true that laws of the United States made in accordance with the Constitution were the supreme law of the land, but in this case the federal statute was a local law intended for the governance of the federal district. Supremacy did not attach to this type of local legislation.

Cohens is important for its jurisprudential and procedural holdings, but Marshall also expanded his definition of federalism in the course of rendering his opinion. He took a careful look at the process by which the Constitution operated, always keeping in mind that the framers were intent upon creating a federal government that would work effectively. He also set forth his view of the division of sovereignty between the states and the federal government. Although the states retained their sovereignty, the very nature of the Constitution made it clear that vesting authority in the United States worked to limit the sovereign power of the states. Furthermore, the framers of the Constitution wisely made provision for restraining state actions that would arrest or impede the enforcement of federal laws. Those provisions required that the Supreme Court take judicial action so that sovereignty disputes might be peacefully resolved within the federal system. They also required, as in McCulloch, that federal instrumentalities not be impeded in their lawful undertakings by state laws or actions.

John Marshall’s Supreme Court opinions clarified most of the ambiguities concerning federalism in the United States. His reasoning drew upon thoughtful textual analysis, tempered in part by his understanding of the Constitution’s history, and also by familiarity with the thinking of its framing fathers. At the same time, Marshall’s eminently practical mind also asked the pragmatic question as to how such a federated government could operate efficiently and peacefully. Not surprisingly, he most frequently employed judicial power to both define and allocate federal and state sovereignty. At the same time he was acutely aware of the political basis for American government, pointing out that governments derived their powers from the consent of the electorate that chose them. For that reason, federalism demanded that no state’s electorate or their government should presume to dictate how the federal electorate’s government should operate. Federal authority, though limited in scope, was supreme because it represented the will of the people of the United States as expressed in their Constitution, and implemented by statutes and treaties.

Cohens v. Virginia; Commerce among the States; Contract Clause; Dartmouth College v. Woodward; Fletcher v. Peck; Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee; McCulloch v. Maryland; Necessary and Proper Clause; U.S. Supreme Court

Bibliography

Robert K. Faulkner, The Jurisprudence of John Marshall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970); Charles F. Hobson, The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996); Herbert A. Johnson, The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall, 1801–1835 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997); and R. Kent Newmyer, John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001).