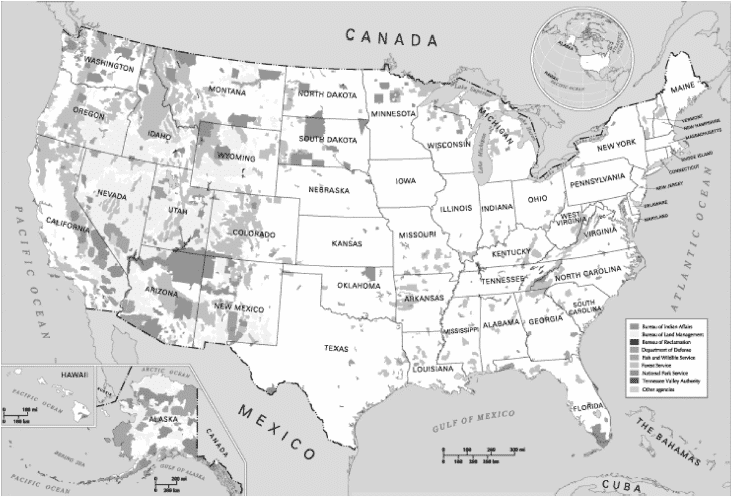

There are over 573 million acres of land in the federally held public domain. The public lands are some 264 million acres of federal land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), an agency of the Department of the Interior. Over 80 percent of the land that now comprises the United States was once in the public domain. Over the course of the nineteenth century, federal policy was that of land disposal. Land was granted to the states for public purposes, and privately to settlers, veterans, and transportation companies. Such policies of land disposal did not succeed, however, in the arid western states. Homesteaders settled on lands where access to water existed. The resulting pattern of land ownership in many western states was a checkerboard of alternating sections of federal, state, and privately held land. Today 30 percent of the nation’s lands remain in the public domain; nearly all of that land is located in the eleven western states. The percentage of federal land ownership in these states ranges from 82 percent in Nevada to 29 percent in Washington.

Public lands are distinguished from other forms of federal land ownership by the absence of an overriding single purpose that governs their use. National parks, military encampments, and to a lesser extent the Forest Service are designated by Congress for clearly defined specific uses. These lands are subject to very limited regulation by the states in which they are located. In contrast, the public lands are often described, sometimes celebrated, and sometimes condemned for being lands of many uses.

With its vast public land holdings in a largely underpopulated region of the nation, the federal government adopted the policy in the nineteenth century of leasing lands to local ranchers or to prospectors. Traditionally leases were granted for grazing or for mining. Later on, they were also granted for drilling for oil and gas. Still later, access to the lands was granted for hunting, fishing, and other forms of recreation. Policies were developed to maintain watersheds, and some uses were restricted that were judged to have adverse effects on the land. Over the course of the twentieth century, public land-use patterns moved from locally dominant uses, such as grazing, to multiple uses. With this change, locally dominant users such as grazers would be expected to accommodate hunters, hikers, and other recreationists to the public lands as well.

The rise of the environmental movement in the 1960’s and 1970’s and the growing western populations combined to challenge traditional grazing and mining uses. Much federal legislation passed in that era protected these newer uses: the national Environmental Policy Act of 1970, which required environmental impact statements for major federal actions significantly affecting the environment; the Endangered Species Act of 1973; and, most importantly, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976. The FLPMA enshrines the doctrine of many uses and values for the public lands; it is the framework for the BLM.

The federal government’s renewed interest in the public lands was often unsettling to a number of western states. Residents of these states saw the growing numbers of federal regulatory initiatives as both a threat to traditional land-use patterns and a challenge to state regulatory authority. In the late 1970’s and into the early 1980’s, in what became known as the Sagebrush Rebellion, a number of western states enacted legislation claiming the public lands as state land. The “rebellion” died out with the advent of the Reagan administration, which was perceived to be sympathetic to traditional uses of the public lands. Many risk-averse Westerners concluded that massive land transfer to the states could have adverse consequences for a wide range of western interests.

Conflict between the federal government and the western states has been endemic for well over a century and is likely to continue for a long time to come. Several explanations underlie the recurrent conflicts between the public land states (states carved out of federally owned territory) and the federal government. In addition to federal authority, states also have a good deal of regulatory latitude over land use. Federal and state land-use regimes regularly bump up against one another. The checkerboard pattern of widely dispersed state parcels has made it difficult for states to develop land-use development strategies. In the 1980’s, there were movements to consolidate state and federal land holdings, primarily to facilitate efforts by the states to increase revenue from their holdings. Such exchanges have been complicated by judgments of comparable value and appropriate uses. A number of western policy makers have long believed that the vast scale of federal land ownership has obstructed the development and diversification of western economies. Finally, a recurring concern in the western states has been the capacity of the federal government (if not always the commitment) to undertake decisive land-use policy shifts for the public lands. Examples range from the Reagan administration’s decision (later withdrawn) to build a vast missile defense system in Nevada and Utah, to the Clinton administration’s creation by executive order of seven national monuments involving hundreds of thousands of acres of public lands, through the reaffirmed commitment by the George W. Bush administration to store nuclear waste at the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada.

The public lands remain a great paradox in American federalism. On both sides of the North Atlantic, it is unusual for a national government to control nearly a third of the nation’s land. It is even more surprising to have a federal government in such a position. This said, it is clear that although public land management is often characterized by conflict, it is nonetheless in many areas an exercise in cooperative federalism. Agreements are regularly renewed between the BLM and state and local authorities. The enduring presence of the public lands is perhaps the strongest evidence for public land management as an exercise in cooperative management. In the long run, few if any major user groups, regardless of their land-use values, support any dramatic change in this area of federal land ownership.

SEE ALSO: Land Use; Reagan, Ronald; Rural Policy; State Government

Bibliography

Charles Davis, Western Public Lands and Environmental Politics (Boulder, CO:Westview Press, 2001); and John G. Francis and Leslie Francis, Land Wars: The Politics of Property and Community (Explorations in Public Policy) (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2003).