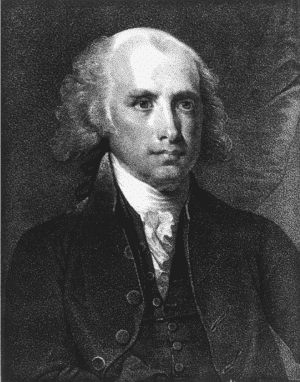

James Madison (1751–1836) contributed to nearly every important phase of the creation of the United States. The eldest of ten children in a moderately wealthy, slaveholding plantation family, he lived his entire life at the family estate, Montpelier, in Orange County, Virginia. At five feet four inches, he was uncommonly short and frail, often in fear for his health. He studied the Scottish Enlightenment at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) in 1769–72 under its president, John Witherspoon. Afterward, he rejected careers in law and the clergy. In 1794, he married Philadelphia widow Dolley Payne Todd.

In 1774, Madison was elected to the Orange County revolutionary Committee of Safety. As delegate to the 1776 Virginia constitutional convention, Madison had the state’s “Declaration of Rights” altered to favor “free exercise of religion” over mere “religious toleration.” He served in Virginia’s executive branch until being elected to the Continental Congress (1779–83), where uncooperative states fueled his cynicism about them and the union. In the Virginia legislature (1784–86) he failed to reform the state’s 1776 Constitution and its financial commitment to the continental government. He did, however, facilitate passage of Virginia’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786) by publishing his objections to public financing of specific religions in “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments” (Hutchinson et al. 1785). Drafted by Thomas Jefferson in 1777, the statute presumed the dependence of democracy upon religious freedom.

Madison’s frustrations with the state and continental governments convinced him of the need for reform. He believed that the populist design of most state constitutions produced bad law and made constitutional reform unlikely. Consequently, by 1785 he came to agree with George Washington and Alexander Hamilton that reform of the Articles of Confederation was necessary.

Madison’s contributions to the Philadelphia Convention (1787) include persuading Washington to serve as presiding officer and his comprehensive notes on the debates, published posthumously in 1840 (Hutchinson, Rachal, Rutland et al. 1962–91). He is known as “the father of the Constitution” for leading his fellow Virginians to set the Convention’s agenda with the Virginia Plan.

The Virginia Plan proposed to replace, rather than revise, the Articles of Confederation. The most powerful of three separate branches would be a bicameral legislature with representation apportioned in each house on the basis of population or tax contributions. The executive and judicial branches would occasionally constitute a Council of Revision that could veto federal and state laws, subject to congressional approval. Finally, Congress could exercise all powers “to which the separate states are incompetent” and could compel state compliance with force.

Several compromises in the final version of the Constitution deviated from Madison’s vision of a federal government less dependent upon the states and powerful enough to correct their ill-conceived legislation. He feared that the “Great Compromise” providing for equal representation in the Senate (Article I, Section 3) and thus favoring the small states would allow their legislatures to corrupt congressional judgment through their choice of senators. The limited presidential veto (Article I, Section 7) that replaced his council of revision did not extend to state laws. The independent judiciary (Article III) was not explicitly granted the power of a veto over the states. The broad grant of power to act when the states are “incompetent” was replaced by a specific list of powers (Article I, Section 8) to which Madison painstakingly added. Finally, the power to compel state compliance was relegated to the more ambiguous “National Supremacy Clause” (Article IV).

Despite his doubts, Madison coordinated supporters of ratification throughout the states. He defeated efforts by Virginia Anti-Federalists, led by Patrick Henry, to condition their ratification on amendments to the original Constitution. His contributions to The Federalist Papers, written in collaboration with Hamilton and John Jay, are considered the best original statement of American constitutionalism. He famously argued that the “extended republic” created by the Constitution would limit the threat to liberty of the “mischief of faction” endemic to “popular government” (The Federalist No. 10). “Ambition” in each of the branches would check the encroachment of one upon the other, thereby limiting national power (The Federalist No. 51). Finally, he reassured Anti-Federalists that the states’ role in constituting the national government and its limited enumerated powers would protect their independence (The Federalist No. 39).

Madison won a seat in the First Congress promising to introduce a Bill of Rights, despite his fear that it would serve to weaken those rights not mentioned. He kept his promise in part to avoid a second convention proposed by some Anti-Federalists.

Treasury Secretary Hamilton’s nationalist economic policies challenged Madison’s federalist views and led him to found, with Jefferson, the first political party. In particular, the “Republicans” opposed the federal “assumption” of state and individual war debts, favorable trade with Great Britain, and the chartering of a national bank. Madison urged strict construction of the Constitution’s enumerated powers against the bank bill. But Hamilton persuaded Washington to sign it.

Discouraged by Federalist control of the national government, Madison “retired” to Virginia in 1797. In 1798, he and Jefferson drafted, respectively, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions challenging the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts. Madison intended these state statutes to arouse public opinion (interposition), whereas Jefferson felt states could legally nullify unconstitutional federal laws (nullification).

As Jefferson’s secretary of state (1801–9), Madison oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, whose constitutionality he ascribed to the treaty power, and struggled to avoid conflict with Europe. He was party to the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison (1803) that established judicial review of federal laws and subsequently state laws (McCulloch v. Maryland 1819).

Madison’s presidency (1809–17) was consumed by diplomatic crises, culminating in war with England (1812–15). Despite his earlier constitutional objections, he proposed and signed legislation chartering the Second National Bank. In retirement, he expressed alarm at the slavery issue and opposed both the Missouri Compromise and the nullification doctrine.

When he died in 1836, Madison had outlived all of his fellow Founding Fathers.

SEE ALSO: Continental Congress; The Federalist Papers; Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions; Virginia Plan

Bibliography

William T. Hutchinson, William M. E. Rachal, Robert Allen Rutland et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison, 17 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962–91); James Madison, The Mind of the Founder: Sources of the Political Thought of James Madison, ed. Marvin Myers (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973); Jack N. Rakove, James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (New York: Harper Collins, 1990); and Garry Wills, James Madison (New York: Times Books, 2002).