Benjamin Franklin was the most original and versatile of the founders in his Federalist ideas. Impressed by the nearby Iroquois Confederation and by the success of the Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union of 1707, he advocated federal and parliamentary unions throughout his political career.

Franklin launched the idea of a union of all the colonies in 1754, at the first major Congress of the Colonies in Albany, to strengthen the empire against the French: the idea of union thus arose first out of imperial exuberance, and was prior to the idea of independence. He proposed in the 1760s colonial representation in London, which would have constituted an imperial parliament for managing the common business of the empire. He offered a first draft of the Articles of Confederation to the Continental Congress. He participated actively in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The Constitution’s drafting completed, he urged upon a Parisian friend a united states of Europe. After the Constitution was ratified, he wrote an antislavery treatise; ultimately abolition would prove necessary for deepening the union into one of equally free and mobile citizens, although in the interim the issue spelled division. He died in the next year, on April 17, 1790.

Franklin’s Albany Plan was the first to make union of the colonies a serious issue. He published a cartoon, “Join or Die,” and later remarked, “We must all hang together or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” With time, however, the meaning of the union changed. Initially it was to be a union within the British Empire, for the sake of strengthening it through a two-tiered structure with an American legislative council and an imperial parliament in London. Later, the idea became one of a union of the colonies for resistance to impositions from the British Parliament. In this form, the union came gradually into being.

As the dispute between the colonies and Britain deepened, Americans came to reject the idea of representation in the British Parliament. Franklin, after urging the idea upon the British, belatedly renounced it, leaving it to his old friend Joseph Galloway and those later spurned as Tories. In his mission to France, he worked long and ultimately successfully for an alliance against Britain—the reverse of his plan at Albany for a union against France. His ultimate peace treaty with England largely vitiated the French alliance; his final federalism was American and neutral.

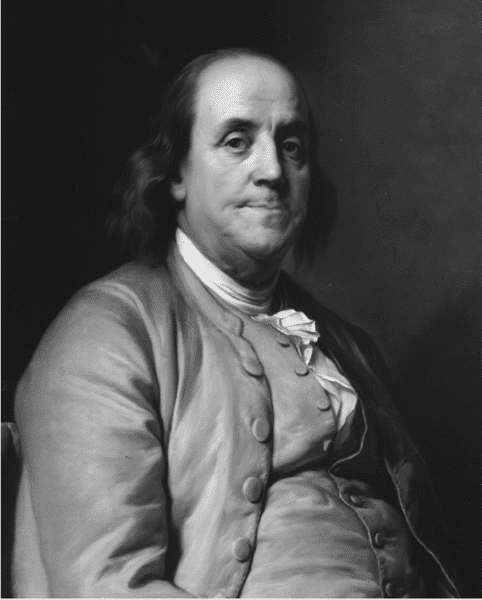

Franklin had a special relation to the Enlightenment. A self-made man born in 1706, he rose from a printer to become a writer, philosopher, inventor, scientist, and political leader. His discoveries on electricity made him famous throughout Europe; his embrace of Voltaire, during his mission to France, was a high point in Enlightenment symbolism.

The liberation of humans and their reconciling for cooperation were the two great themes of Franklin’s political life, in this embodying with a unique directness the cause of the Enlightenment philosophies. Thus he focused his key projects on consolidating and expanding what he saw as the empire of freedom. He feared lest the fragile pottery of the British Empire would be cracked, and so it was. His hopes remained for the American half, in which he saw the greater future. Those hopes rested with the new union, itself also fragile.

George Washington remarked, in his first farewell address as commander in chief in 1783, that the United States’ success or failure after independence would determine the fate and reputation of freedom for ages to come, and that its success depended on reinforcing the Union. Franklin shared the outlook. It was no longer a matter of union against an external enemy, but to make good on the internal promise of the United States. The hopes of the Enlightenment would rise or fall with this refined American federalism.

At the close of the Constitutional Convention, nearing the close of his life, Franklin said (as recorded by James Madison) that he had often wondered, in the course of the Convention “and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue,” whether the Sun of America “was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.” His optimism strengthened, he wrote in October 1787 to a friend in Paris (Ferdinand Grand) that “[i]f (the Constitution) succeeds, I do not see why you might not in Europe carry good Henry the 4th the Project of into Execution, by forming a Federal Union and One Grand Republick.” France’s King Henry the Fourth envisioned a United Europe dubbed the “Grand Design.” One hundred and sixty years later, Americans would pressure Europeans into beginning to do this with the Marshall Plan.

Franklin’s cosmopolitanism survived a rough political life; in a letter of December 4, 1789, he wrote (to David Hartley), “God grant, that not only the Love of Liberty, but a thorough Knowledge of the Rights of Man, may pervade all the Nations of the Earth, so that a Philosopher may set his Foot anywhere on its Surface, and say, ‘This is my Country.’ ”

SEE ALSO: Albany Plan; Constitutional Convention of 1787; Continental Congress