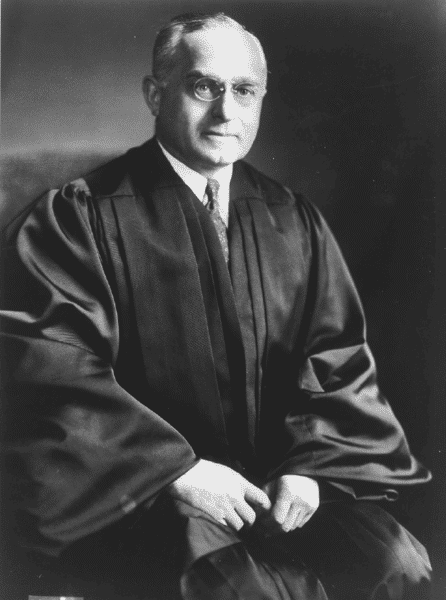

No person rose from more humble beginnings, was more brilliant, and seemed more fully prepared for service on the Supreme Court than Felix Frankfurter. However, his career on the Court, especially on questions of federalism, has sparked debate among scholars and observers. Frankfurter’s personal neuroses and frequently enigmatic, conservative judicial posture on many federalism issues surprised, and ultimately disappointed, many of the liberal supporters of the president who appointed him, Franklin D. Roosevelt. In doing so, though, he also established a model for judicial self-restraint, and states’ rights–oriented decisions, that won him legions of judicial followers.

Felix Frankfurter arrived in the United States from his native Austria in 1894, at the age of 12, without being able to speak a word of English. Remarkably, just 11 years later he graduated as the valedictorian from Harvard Law School. After stints in a prominent New York City law firm, the U.S. attorney’s office in New York, and the War Department as the counsel for the Bureau of Insular Affairs, Frankfurter was asked in 1914 to join the faculty of Harvard Law School. Eventually he would be named the Byrne Professor of Administrative Law, become close friends with self-restraint-oriented Supreme Court Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis D. Brandeis, and write so many influential law books that he would become recognized as one of the foremost legal scholars in the United States.

Having experienced anti-Semitism in his earlier career, Frankfurter found that his Jewish religion put him at odds once again with the puritanical Brahmin Harvard administration and Boston society. Nevertheless, Frankfurter showed tremendous courage and compassion, supplementing his legal academic work with nonprofit Progressive legal reform work for a variety of causes. Working sometimes at the suggestion and with the financial support of then–Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis, Frankfurter argued the Oregon as well as Washington, D.C., minimum wage law cases before the Court, argued on behalf of accused bomber Tom Mooney to President Woodrow Wilson, joined and then left the religious reformist Zionist Organization, defended law school colleague Zechariah Chafee who was being attacked by conservative Harvard alumni, and argued the appellate case of convicted payroll robbery murderers and anarchists Niccola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Despite all of the controversy surrounding these activities, Frankfurter was offered a seat on the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, which he declined.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president, Frankfurter turned down the U.S. solicitor generalship, helped to draft the revolutionary Securities Act, and resisted all other formal government appointments. Instead, he became a powerful informal adviser to the president on both policy and personnel selection. In time, the New Deal was staffed with legions of what were termed “Felix’s Happy Hot Dogs,” giving Frankfurter even more influence over public policy.

After his appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1939, replacing Benjamin N. Cardozo in what came to be known as the “Jewish Seat” on the Court, Frankfurter seemed poised to take a leadership position that would direct the other justices in a liberal, New Deal direction and possibly even end with his elevation to the chief justiceship. But such was not to be. Frankfurter instead adopted a conservative, states’ rights–oriented, self-restraint position on civil liberties issues, which ultimately separated him jurisprudentially from the other liberals on the Court. In addition, his backstage manipulation on the Court separated him from them personally and led to long-term feuds that prevented him from amassing long-term conservative majorities on many of the issues most important to him.

Early on the Court, Frankfurter seemed to be supportive of the state and national government’s position in wartime policies, supporting the forced flag salute of public school children over their First Amendment religious objections and the ill-advised Japanese internment policy over due process and equal protection rights claims by litigants. However, when it came to the issue of extending the Bill of Rights’ protection to the states, thus enabling the national judiciary to supervise and make more uniform the actions of the state judiciary, Frankfurter developed a more states’ rights position. For him, these civil liberties issues were best left to the interpretations of various state judges to define the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Thus, the answers to various political questions were to be left either to the states, the level of government closest to the people serving as what Justice Brandeis called the “laboratories for democracy,” or to the elected political branches, rather than the appointed, life-tenured judges. Thus, for him, rather than extend the full protection of the Fourth Amendment’s “search and seizure,” the Fifth Amendment’s “self-incrimination,” the Sixth Amendment’s “right to counsel,” and the Eighth Amendment’s “cruel and unusual punishment” provisions to the states, thus protecting defendants’ rights, Frankfurter was much more protective under the Fourteenth Amendment’s “Due Process Clause” of the state’s determination of individuals’ rights, barring only government actions that “shocked his conscience.” Similarly, when the national government was asked to use the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause to supervise the reapportionment efforts of state legislatures, Frankfurter argued that this was not an area for judicial regulation, but rather was to be decided by a political remedy. While Frankfurter did support the national government’s power to desegregate the public schools in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, once again he argued behind the scenes for a more limited interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection power. As a result of these and other states’ rights decisions, Frankfurter the reformist lawyer came to be seen as Frankfurter the conservative judge. Only after he was compelled to retire from the Court in 1962 after suffering a devastating stroke, and was replaced by a reliable liberal, judicial activist, John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg, was the fifth vote added to the liberals on the Court that enabled the revolutionary liberal activist Warren Court to more fully extend the national judicial power to the states.

Frankfurter’s legacy on the Court did not end after his death in 1965; rather, he established a constitutional foundation for the states’ rights position on federalism issues that continues to influence modern American constitutional law.

SEE ALSO: Fourteenth Amendment; Incorporation (Nationalization) of the Bill of Rights; U.S. Supreme Court

Bibliography

H. N. Hirsch, The Enigma of Felix Frankfurter (New York: Basic Books, 1981); Joseph P. Lash, From the Diaries of Felix Frankfurter (New York: W.W. Norton, 1975); Bruce Allen Murphy, The Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection: The Secret Political Activities of Two Supreme Court Justices (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982); and Michael E. Parrish, Felix Frankfurter and His Times: The Reform Years (New York: Free Press, 1982).