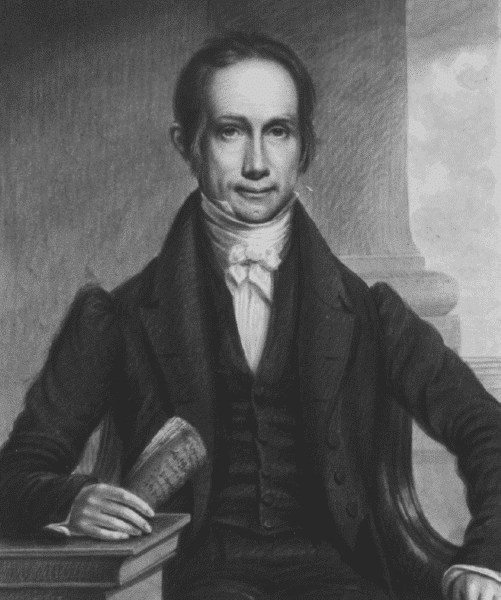

Henry Clay, of Lexington, Kentucky, was a national leader who was one of the founding fathers of the Whig Party and also known as the “Sage of Ashland” and the “Great Compromiser.” Member of the Kentucky General Assembly, five-term U.S. senator, and six-term member of the U.S. House of Representatives, of which he served as speaker of the House from 1811 to 1820 and from 1823 to 1825, he was also a candidate for president in 1824 and 1832 for the Federalist and National Republicans, and in 1844 for the Whigs. Clay was also U.S. secretary of state from 1825 to 1829. His extensive public service positioned him in key leadership roles during the development of the early republic, and Clay impacted the development of federalism in two important policy areas, economic development and states’ rights. Despite the enduring legacy of Henry Clay’s economic plan, termed the American System, his political leadership placed him in difficult circumstances to win the presidency and build the national consensus he desired for his Whig program.

Clay was the primary architect of the American System. The American System had three essential components: federal aid for internal improvements, a protective tariff for industry, and a national bank. The American System provided an urbanist model of economic growth that contrasted with the rural model of Jeffersonians, and the economic policy theory behind it promoted nationalism at the expense of states’ rights. Clay’s American System established the foundation of modern economic development policy and defined strong national government powers as essential for securing the economic prosperity of strong national commercial enterprises.

Henry Clay was known as the Great Compromiser because of his role in mitigating the increasing conflict in the federal system between slave and free states. This was a critical role Clay played when Missouri’s application for statehood created a federalism crisis. Clay supported a compromise: allowing slavery to continue in Missouri but otherwise prohibiting it North of the 36 degree 30 minute latitude. When the controversy again erupted over Missouri’s attempt to prohibit the movement of free blacks, Clay emerged in 1821 as the leader of the second Missouri Compromise, whereby Missouri agreed not to deprive a citizen from another state of equal rights and privileges. After the Mexican War, which Clay opposed, he was elected to the U.S. Senate from Kentucky and introduced the Compromise of 1850 to deal with the crisis over the extension of slavery into the areas of California and New Mexico acquired from Mexico. Clay’s death in 1852 left a void in national leadership that contributed to the ultimate crisis of federalism in 1860.

SEE ALSO: American System; Civil War; Compromise of 1850; Internal Improvements; Jackson, Andrew; Missouri Compromise of 1820; Secession; Slavery

Bibliography

Maurice G. Baxter, Henry Clay and the American System (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1995); Richard Chambers, Speeches of the Hon. Henry Clay, of the Congress of the United States (Cincinnati, OH: Shepard & Stearns, 1842); Robert V. Remini, Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (New York:W.W. Norton, 1991); and Kimberly C. Shankman, Compromise and the Constitution: The Political Thought of Henry Clay (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 1999).