Imagine a bully threatening you and others at a school where administrators refuse to intervene. Standing up to the bully alone is impossible. Stopping the bully is more likely if you unite with others. But how can you be sure the others will come to your aid when needed, or not turn the group against you? How much individual liberty would you relinquish to the group to work collectively toward your common interests? The challenge of preserving individual liberty while also fostering collective action is common. The American people, after declaring independence from Britain in 1776, faced a similar dilemma. Their solution resulted in what has come to be known as a federal system of government.

Why Federalism?

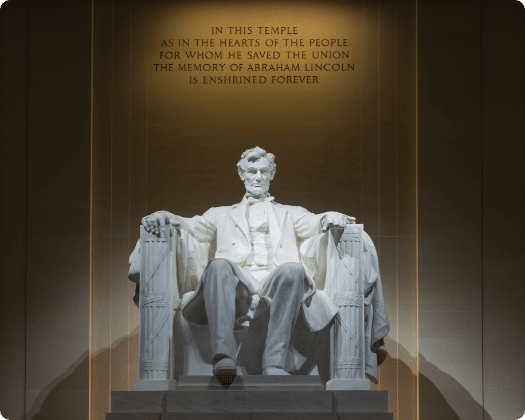

The founders realized that government is necessary to protect human rights but wanted to prevent the rise of dictatorial rule characteristic of most governments past and present. A bill of rights, a parchment barrier, would not be sufficient to protect those rights. Instead, government had to be structured through federalism and separations of powers to check the autocratic designs of ambitious politicians.

Modern federalism, invented by the American founders, divides and shares powers to allow everyone to participate in governing the whole country for limited purposes of unity, while also guaranteeing self-government to the people’s constituent states, thereby preserving diversity. Today, nearly half the world’s people live in federal countries.

Where is Federalism in the Constitution?

Content is forthcoming

Who Was Publius — The Real Guy?

“Publius” was the pseudonym used by the authors of The Federalist, which was written to persuade the citizens of New York to support ratification of the U.S. Constitution. “Publius” was a fairly common praenomen (the first or personal name) of an ancient Roman. Some readers of The Federalist, therefore, might have understood “Publius” to be the Publius praised in the Acts of the Apostles (28:7), “the chief man of the island” of Melita (probably Malta) who received and lodged Paul and his shipwrecked companions for three days. Most readers, however, probably recognized “Publius” as Publius Valerius Publicola, a Roman patriot, general, and statesman who lived in the sixth century B.C.E. and who, according to Plutarch’s Lives, saved the early Roman republic several times from tyranny and military subjugation. Publius was one of the founders of the republic. His republican reputation was regarded by some of the American founders as superior to the republican bona fides of Brutus and Cato.

Federalism Explained

What is Federalism?

Federalism is both a form of government and a principle. It is a voluntary form of government and mode of governance that establishes unity while preserving diversity by constitutionally uniting separate political communities (e.g., the 13 original U.S. states) into a limited, but encompassing, political community (e.g., the United States) called a federal polity. As a principle, federalism combines self-rule and shared rule by linking individuals and groups in lasting but limited union thereby providing for the energetic pursuit of common ends while seeking to sustain the integrity of each partner, check forces of centralization and anarchy, establish justice among the consenting partners, and ensure individual and community liberty. See more.

Constitution and Rule of Law

The word “federal” comes from the Latin word foedus, meaning covenant, pact, or treaty. The formulators of federalism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries envisioned a government based on covenant between agreeing parties with that relationship defined in a written constitution. In modern times, most federal unions are confirmed through a perpetual covenant of union embodied in a written constitution. That written constitution outlines, among other things, the terms by which power is divided or shared in the political system. Typically, the constitution can be altered only by extraordinary procedures, such as supermajority votes. Moreover, the constituent polities sometimes retain local constitution-making rights of their own.

Hierarchy and Scope

Federalism unites separate polities into an overarching political system that allows each to maintain its fundamental political integrity. Federal systems do this by dispersing power among general and constituent governments. Consequently, interactions between these different governments are not based on a hierarchy of superior-subordinate relationships but rather upon interactions between co-sovereigns with independent integrity and autonomy within their respective territorial spheres of authority..

Both the general government and the constituent governments have constitutional authority to govern individuals directly (e.g., regulate behavior and levy taxes), and each has final decision-making authority over certain constitutionally delegated or reserved matters. Some constitutional powers belong exclusively to the general government; others belong exclusively to the constituent governments. Still others are concurrent—that is, exercised by both the general and constituent governments.

Unity and Diversity

Federalism provides a basis to unify diverse partners into a common community to address common issues; however, by limiting the powers of that general government, federalism protects local self-government so the participating members’ differences, diversity, and autonomy can be reflected in the laws and policies govern their own lives. Maintaining a healthy balance between unity and diversity is important because too much unity can suppress diversity and autonomy while too much diversity can become divisive, resulting in separation and disunion.

Shared-Rule and Self-Rule

Federalism uses covenants to deliberately join humans together as equals bound to certain collective endeavors while preserving their respective integrities. Such a covenant often creates a new entity (e.g., the general government) with defined powers and responsibilities, but its powers are limited, thus protecting the integrity, and a realm of autonomy, for the covenanting partners. By joining partners together in a collective enterprise, federalism fosters shared governance, or shared-rule, on collective issues of unity. That is, all the constituent political communities share in governing the entire federation. By preserving a measure of autonomy for the covenanting partners, federalism also protects self-rule. The combination of shared-rule and self-rule is the basis of self-governance on a large scale.

Non-Centralization

Federal systems are, in principle, noncentralized. In a decentralized unitary system, the central government can unilaterally centralize or decentralize power. In a noncentralized federal system, both the general federation government and the constituent political communities must act coordinately to centralize or decentralize power. A federal constitution diffuses power between the general government and constituent units, grants each government near equality in their respective responsibilities and powers, and protects those constitutional powers from being taken away from either one without mutual consent. Thus, constituent political communities may participate as partners in national government activities and also act unilaterally with a high degree of autonomy in areas constitutionally open to them—even on crucial questions and, to a degree, in opposition to national policies, because they possess effectively irrevocable powers.

When power is noncentralized in a federal government, it is inaccurate to refer to the different governments as “layers” or “levels”, which imply that one government (such as the national government) is “higher” or superior and the other governments are “lower” or inferior. It is more accurate to refer to the various governments in a noncentralized system as “orders” or “planes” of government.

Choice and Consent

Federalism, conceived in the broadest social sense, looks to the linkage of people and institutions by mutual consent, without the sacrifice of their individual identities, as the ideal form of social organization. Federal systems facilitate choice by vesting some political power in constituent units to create their own policies. Other ways federal systems foster choice and consent include:

- Allowing constituent units to create their own policies places many political decisions closer to the people where they have more direct sources of information, more opportunities to participate in the political process, and greater per capita influence;

- Allowing local diversity gives citizens a choice to move to localities where government policies may more closely represent their interests and values;

- When one government fails to respond, citizens may call upon another government to check or correct those errors;

- In the United States, the electoral college and equal representation in the Senate seek to ensure that territorial (i.e., states) and national minorities are not swamped by national majorities.

Cooperation

Most federal polities experience widespread relations among their governments called intergovernmental relations. These may entail relations between the general and constituent governments, as well as local governments, among the constituent governments themselves (e.g., interstate relations in the United States), between the constituent governments and their local governments (e.g., state-local relations in the United States), and relations among local governments themselves (e.g., interlocal relations). Ideally, intergovernmental relations are cooperative, collaborative, and competitive with mutual coordination and adjustment. However, partisan differences, personal ambition, social movements, and many other factors can make intergovernmental relations collusive, cooptive, conflictual, and/or coercive.

Competition

Because federalism creates two or more semiautonomous governments, federalism elicits competition both interjurisdictionally (horizontal) and intergovernmentally (vertical). Competition prevents monopoly government, which has little or no incentive to cooperate and may limit diversity and liberty. Competition can induce governments to be more efficient and responsive to their public. Interjurisdictional competition fosters liberty by allowing people to “vote with their feet” and move to the jurisdictions that match their values and desired balance between taxes and government services. Theoretically, interjurisdictional competition may create a “race to the bottom” whereby, for example, they battle against each other to reduce their taxes and regulations to attract businesses. There is little evidence for races to the bottom; instead, interjurisdictional competition often induces governments to make their jurisdictions more efficient and inviting to people and businesses.

Bargaining and Negotiation

In a federal system, each order of government (the national government and constituent governments) is supreme and sovereign within the limited powers and responsibilities assigned it by the country’s constitution. There is, however, no superior government to direct and coordinate activities when problems require input from multiple orders of government or one government needs the assistance of another to accomplish its goals. Rather than a superior government commanding and controlling subordinate governments, coordination between governments in federal systems ordinarily requires bargaining and negotiation between equal, or nearly equal, powers.

Bargaining and negotiation in federal systems often occur at the policy formulation, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation stages – both intergovernmentally (e.g., between the national and state governments) and interjurisdictionally (e.g., between states). The non-centralized, non-hierarchical character of federal systems means that coordinated operations are often characterized by a measure of disorder. This fits federalism’s origin in covenants between equals as a means to coordinate actions while maintaining the integrity and independence of each.

Federal Political Culture

The essence of federalism, some claim, lies not in the institutional or constitutional structure but in the attitudes of its citizens. Those attitudes require a commitment to federalism itself and its values of partnership, comity, unity in diversity, shared-rule, and self-rule. A deep commitment to these attitudes and values creates an underlying culture that values federalism as an idea and primary goal in its own right. Such a culture creates federalism “mores” or understandings of acceptable and unacceptable behavior necessary for sustaining a federal system. In other words, paper constitutions and institutional checks and balances will not preserve federalism if society does not possess a “federal political culture” that identifies federalism as a fundamental, constitutional value that requires accommodating and balancing against other constitutional values. When done well this cultivates a deep public sentiment that unites the nation and transcends ephemeral public opinion on individual or partisan issues.

Federalism Explained

What is Federalism?

Federalism is both a form of government and a principle. It is a voluntary form of government and mode of governance that establishes unity while preserving diversity by constitutionally uniting separate political communities (e.g., the 13 original U.S. states) into a limited, but encompassing, political community (e.g., the United States) called a federal polity. As a principle, federalism combines self-rule and shared rule by linking individuals and groups in lasting but limited union thereby providing for the energetic pursuit of common ends while seeking to sustain the integrity of each partner, check forces of centralization and anarchy, establish justice among the consenting partners, and ensure individual and community liberty. See more.

Constitution and Rule of Law

The word “federal” comes from the Latin word foedus, meaning covenant, pact, or treaty. The formulators of federalism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries envisioned a government based on covenant between agreeing parties with that relationship defined in a written constitution. In modern times, most federal unions are confirmed through a perpetual covenant of union embodied in a written constitution. That written constitution outlines, among other things, the terms by which power is divided or shared in the political system. Typically, the constitution can be altered only by extraordinary procedures, such as supermajority votes. Moreover, the constituent polities sometimes retain local constitution-making rights of their own.

Hierarchy and Scope

Federalism unites separate polities into an overarching political system that allows each to maintain its fundamental political integrity. Federal systems do this by dispersing power among general and constituent governments. Consequently, interactions between these different governments are not based on a hierarchy of superior-subordinate relationships but rather upon interactions between co-sovereigns with independent integrity and autonomy within their respective territorial spheres of authority..

Both the general government and the constituent governments have constitutional authority to govern individuals directly (e.g., regulate behavior and levy taxes), and each has final decision-making authority over certain constitutionally delegated or reserved matters. Some constitutional powers belong exclusively to the general government; others belong exclusively to the constituent governments. Still others are concurrent—that is, exercised by both the general and constituent governments.

Unity and Diversity

Federalism provides a basis to unify diverse partners into a common community to address common issues; however, by limiting the powers of that general government, federalism protects local self-government so the participating members’ differences, diversity, and autonomy can be reflected in the laws and policies govern their own lives. Maintaining a healthy balance between unity and diversity is important because too much unity can suppress diversity and autonomy while too much diversity can become divisive, resulting in separation and disunion.

Shared-Rule and Self-Rule

Federalism uses covenants to deliberately join humans together as equals bound to certain collective endeavors while preserving their respective integrities. Such a covenant often creates a new entity (e.g., the general government) with defined powers and responsibilities, but its powers are limited, thus protecting the integrity, and a realm of autonomy, for the covenanting partners. By joining partners together in a collective enterprise, federalism fosters shared governance, or shared-rule, on collective issues of unity. That is, all the constituent political communities share in governing the entire federation. By preserving a measure of autonomy for the covenanting partners, federalism also protects self-rule. The combination of shared-rule and self-rule is the basis of self-governance on a large scale.

Non-Centralization

Federal systems are, in principle, noncentralized. In a decentralized unitary system, the central government can unilaterally centralize or decentralize power. In a noncentralized federal system, both the general federation government and the constituent political communities must act coordinately to centralize or decentralize power. A federal constitution diffuses power between the general government and constituent units, grants each government near equality in their respective responsibilities and powers, and protects those constitutional powers from being taken away from either one without mutual consent. Thus, constituent political communities may participate as partners in national government activities and also act unilaterally with a high degree of autonomy in areas constitutionally open to them—even on crucial questions and, to a degree, in opposition to national policies, because they possess effectively irrevocable powers.

When power is noncentralized in a federal government, it is inaccurate to refer to the different governments as “layers” or “levels”, which imply that one government (such as the national government) is “higher” or superior and the other governments are “lower” or inferior. It is more accurate to refer to the various governments in a noncentralized system as “orders” or “planes” of government.

Choice and Consent

Federalism, conceived in the broadest social sense, looks to the linkage of people and institutions by mutual consent, without the sacrifice of their individual identities, as the ideal form of social organization. Federal systems facilitate choice by vesting some political power in constituent units to create their own policies. Other ways federal systems foster choice and consent include:

- Allowing constituent units to create their own policies places many political decisions closer to the people where they have more direct sources of information, more opportunities to participate in the political process, and greater per capita influence;

- Allowing local diversity gives citizens a choice to move to localities where government policies may more closely represent their interests and values;

- When one government fails to respond, citizens may call upon another government to check or correct those errors;

- In the United States, the electoral college and equal representation in the Senate seek to ensure that territorial (i.e., states) and national minorities are not swamped by national majorities.

Cooperation

Most federal polities experience widespread relations among their governments called intergovernmental relations. These may entail relations between the general and constituent governments, as well as local governments, among the constituent governments themselves (e.g., interstate relations in the United States), between the constituent governments and their local governments (e.g., state-local relations in the United States), and relations among local governments themselves (e.g., interlocal relations). Ideally, intergovernmental relations are cooperative, collaborative, and competitive with mutual coordination and adjustment. However, partisan differences, personal ambition, social movements, and many other factors can make intergovernmental relations collusive, cooptive, conflictual, and/or coercive.

Competition

Because federalism creates two or more semiautonomous governments, federalism elicits competition both interjurisdictionally (horizontal) and intergovernmentally (vertical). Competition prevents monopoly government, which has little or no incentive to cooperate and may limit diversity and liberty. Competition can induce governments to be more efficient and responsive to their public. Interjurisdictional competition fosters liberty by allowing people to “vote with their feet” and move to the jurisdictions that match their values and desired balance between taxes and government services. Theoretically, interjurisdictional competition may create a “race to the bottom” whereby, for example, they battle against each other to reduce their taxes and regulations to attract businesses. There is little evidence for races to the bottom; instead, interjurisdictional competition often induces governments to make their jurisdictions more efficient and inviting to people and businesses.

Bargaining and Negotiation

In a federal system, each order of government (the national government and constituent governments) is supreme and sovereign within the limited powers and responsibilities assigned it by the country’s constitution. There is, however, no superior government to direct and coordinate activities when problems require input from multiple orders of government or one government needs the assistance of another to accomplish its goals. Rather than a superior government commanding and controlling subordinate governments, coordination between governments in federal systems ordinarily requires bargaining and negotiation between equal, or nearly equal, powers.

Bargaining and negotiation in federal systems often occur at the policy formulation, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation stages – both intergovernmentally (e.g., between the national and state governments) and interjurisdictionally (e.g., between states). The non-centralized, non-hierarchical character of federal systems means that coordinated operations are often characterized by a measure of disorder. This fits federalism’s origin in covenants between equals as a means to coordinate actions while maintaining the integrity and independence of each.

Federal Political Culture

The essence of federalism, some claim, lies not in the institutional or constitutional structure but in the attitudes of its citizens. Those attitudes require a commitment to federalism itself and its values of partnership, comity, unity in diversity, shared-rule, and self-rule. A deep commitment to these attitudes and values creates an underlying culture that values federalism as an idea and primary goal in its own right. Such a culture creates federalism “mores” or understandings of acceptable and unacceptable behavior necessary for sustaining a federal system. In other words, paper constitutions and institutional checks and balances will not preserve federalism if society does not possess a “federal political culture” that identifies federalism as a fundamental, constitutional value that requires accommodating and balancing against other constitutional values. When done well this cultivates a deep public sentiment that unites the nation and transcends ephemeral public opinion on individual or partisan issues.

Federalism Matters Podcast

Federalism is American government’s best kept secret. Its influence is pervasive and profound. Though not mentioned in the Constitution, federalism’s meaning and application have been at the center of disputes from 1776 to the Civil War to our current culture wars. We are scholars who focus on federalism, and through this podcast, we explore how federalism, from practice to theory, shapes our politics, policies, culture, society, and daily life.

The Federalism Minute

Federalism’s influence on American government, culture and society is pervasive and profound, yet often unexplored. This short podcast examines single, practical topics to show how federalism’s influence is real and relevant in average citizens’ daily lives.